|

History:

Prewar -

1941 -

1942 -

1943 -

1944 -

1945 -

Postwar

The Ship -

All Hands -

Decorations -

Remembrance

Page 2 of 3 < Previous 1 | 2 | 3

| |

Read & Riley: The Combat Photographers' Legacy | |

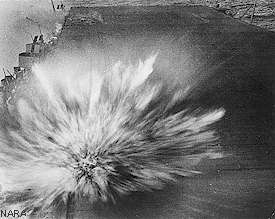

| One of the most famous images of the Pacific War - a bomb caught at the instant it exploded on the Big E's flight deck during the Eastern Solomons battle - has long been attributed to Photographer's Mate Second Class Robert Frederic Read. Read lost his life during the battle of 24 August 1942 and it is widely believed that his final photo was of the bomb that killed him. | |

| While outwardly plausible, the story contradicts the historical record. Enterprise's action report for 24 August 1942 indicates that four photographers were in action during the afternoon attack. Ralph Baker (PhoM 1/c) and Read both operated still cameras: Baker from a point forward of the island, Read from the aft starboard 5" gun gallery, at flight deck level. Marion Riley (PhoM 2/c) manned a motion picture camera from the aft end of the ship's island, above the flight deck. W. Edward Smith (PhoM 2/c) was stationed in the Air Plot, also in the ship's island. | |

| Read, the action report states, photographed the enemy planes as they attacked and were shot down. The first bomb to strike the ship did not deter him, but the second bomb destroyed the gun platform were Read was stationed. Read was killed instantly by this bomb, along with 37 other men. The bomb exploding in the photo was the third to hit the ship, and was photographed from above the flight deck. | |

| Torpedo Ten photographer Joe Houston recently contacted both Smith and Riley's son, Marion Riley III. Ed Smith indicated, and Mr. Riley confirmed, that the photo is Marion Riley's. Riley's camera was damaged by the explosion, but the film survived. A dramatic sequence of stills from the film was published in Life Magazine months after the battle. | |

| Read's legacy is not diminished by this revelation. It appears that at least one of Read's photos survives to this day: that of an enemy plane burning on the sea while the Big E races by just yards away. The ship's rail, the curve of the hull, and the angle of the shot all indicate this photo was taken from the aft starboard quarter of the ship, where Read was stationed. More of Read's photos probably languish in the archives, waiting only for proper identification. | |

| Like the gunners and other men above decks that terrible August afternoon, Read carried out his duties with determination in the face of a withering aerial onslaught. Fate alone determined that Read would die just moments before the creation of the image that symbolizes the courage of a combat photographer. |

The next morning, August 24, a Monday, twenty three Enterprise SBDs fanned out on 200 mile search legs, across a wide arc of ocean north of the Big E's Task Force 16. Hours of tedious searching uncovered no enemy force. Other reconnaissance flights, however, had more success. Around 1000, PBYs reported a carrier, a cruiser and destroyer escort some 200 miles northwest of the American force. The carrier was the light carrier Ryujo, escorted by the cruiser Tone, sent in advance of the main Japanese strike force to cover the transports approaching from Rabaul. Then, fighters from Saratoga intercepted and downed another enemy flying boat, this one only twenty miles from the task force. Early in the afternoon, another Saratoga airman brought down still another enemy scout, this one within visible range of the American ships.

There was no question now that the Japanese knew the location of the American carriers, but with the exception of Ryujo, the Americans could only guess the position of the Japanese. Shortly after 1300, twenty three fighters and dive bombers rumbled down Enterprise's flight deck, launched on 250 mile search legs north and west of the task force.

Another half hour passed with no contacts, other than the PBYs still shadowing Ryujo. Fletcher, after struggling to close the distance between Ryujo and his task forces, grudgingly ordered Saratoga to launch her strike. Just minutes after Saratoga's thirty dive bombers and seven torpedo planes had formed up and struck out towards Ryujo, Navy PBYs and Enterprise scouts unmasked the real threat. Some 200 miles north of Enterprise and Saratoga, Shokaku and Zuikaku were surging southward at 30 knots, preparing to strike a blow against the American carriers. With heavy static disrupting communications on both sides, and inexperienced American pilots cluttering the airwaves with chatter, the reports didn't immediately reach Fletcher.

When they did, he immediately attempted to redirect Saratoga's strike, even as they were lining up the attack which would put Ryujo under the waves by that evening. Every available fighter on both Saratoga and the Big E was gassed, armed and spotted, ready to take off at the first sign of an attack.

The sign came at 1632: on radar, many bogies, range 88 miles, bearing 320 degrees. Saratoga and Enterprise, sailing ten miles apart, turned southeast into the wind and launched their remaining fighters. Aft of Enterprise, matching her 27 knots, steamed the new 35,000 ton battleship North Carolina BB-55; at their flanks the cruisers Portland and Atlanta, with six destroyers in the screen. On all ships, guns were trained skyward, and eyes strained towards the northwest, where - still over the horizon - the enemy was approaching. Overhead circled four-plane fighter sections, fifty-four planes in all.

The first contact with the incoming enemy strike was made at 1655. At 18,000 feet, two miles above the Wildcats scrambling to intercept, were two formations of Japanese Val dive bombers. For almost twenty minutes, Wildcats, Zeros and Vals tangled high over the sea. Afterwards, Enterprise pilots could claim having downed 29 planes: a figure more remarkable because of the inexperience and lack of discipline of the American pilots at that time.

As the aerial battle raged, drifting steadily closer to Enterprise's task force, Enterprise launched her remaining eleven Dauntlesses and six TBFs, on an ultimately fruitless raid against the main Japanese force. The decision to launch the strike, however, suggested by air officer John Crommelin, probably saved Enterprise from a fate like that suffered by the Japanese carriers at Midway. The planes, fully fueled and armed, had been spotted in the same area where, in minutes, three bombs would tear through the Douglas fir planking of Enterprise's flight deck. Had the planes been parked there when the bombs hit, Enterprise likely would not have survived the day.

The last plane lifted off Enterprise's deck at 1708. Her gunners now stood ready to defend the ship. Yet even as Radar Plot reported "The enemy planes are now directly overhead!", task force lookouts could not spot the enemy planes. Worse, the ship's fire control directors failed to pick up the target, depriving the 5" guns the opportunity to fire on the enemy strike group before it could begin its attack. At 1712, as the first of the surviving 30 Val dive bombers nosed over at 20,000 feet, a puff of smoke attracted the attention of 1st Sergeant Joseph R. Schinka (USMC). Commanding the Big E's #4 20mm anti-aircraft battery, Schinka opened fire. Though the enemy planes were still beyond the reach of the 20mm batteries, the gun's tracers guided the fire of other guns. In moments, a thundering barrage of 20mm, 1.1" and 5" fire filled the sky over Enterprise's flight deck, as North Carolina, Portland, Atlanta and the destroyers all came to her defense.

In the clear blue, late afternoon sky, the bombers pitched into their dives, one every seven seconds: five, maybe six planes pressing their attack simultaneously, while others formed up behind them, or sped away low over the waves after releasing their bombs. For nearly two minutes, as Enterprise weaved and bobbed with surprising agility, the heavy anti-aircraft fire took its toll on the attacking planes, Enterprise's guns alone knocking down 15. High overhead, fighters from Saratoga and the Big E made passes at the planes as they prepared for their dives, sometimes even following the Vals during their descent. It wasn't enough. The first bomb to strike Enterprise pierced her flight deck just forward of the aft elevator, plunged through five decks and detonated.

The time was 1714. An elevator pump room team, ammunition handlers, and a damage control team stationed in the chief petty officers' quarters were wiped out by the blast. Thirty five men died instantly. As the explosion spread, it ripped six foot holes in the hull at the waterline: the ship quickly acquired a list to starboard as seawater poured in. The blast tore sixteen foot holes through the steel decks overhead, bulging the hangar deck upwards a full two feet, and rendering the aft elevator useless. The concussion whipped the warship - 800 feet and millions of pounds of wood and steel - stem to stern, first upwards, then side-to-side, hurling men off their feet, out of their chairs, across the gun tubs.

Trailing flames and smoke, a Japanese bomber screams over Enterprise's bridge during the Eastern Solomons battle. |

Ship and crew had just thirty seconds to recover before the second bomb struck. Detonating on impact, just fifteen feet from where the first bomb had punched through the deck, it obliterated the aft starboard 5" gun gallery and its crew, the violence of the explosion amplified by the ignition of powder bags in the gun tub. Thirty eight men, ten of whom were never positively identified, died that moment. The guns of the aft starboard quarter fell silent, their crews dead or wounded; heavy black smoke poured from newly ignited fires.

Trailing smoke, taking on water, Enterprise drove forward at 27 knots. Below decks and across the flight deck, damage control teams scrambled to bring the fires and flooding under control, to pull survivors from the slippery and torn decks and compartments, to restore power and flush holds of explosive vapors. As the ship twisted away from under the continuing assault, her remaining guns resumed fire, rejoining the barrage thrown up by North Carolina and the other ships in the task force. For almost ninety long seconds the task force fought back against the aerial assault, protecting the precious flat deck at its center.

Image Library -

Action Reports and Logs -

News Stories

Message Boards -

Bookstore -

Enterprise CV-6 Association

Copyright © 1998-2003 Joel Shepherd ([email protected])

Sources and Credits